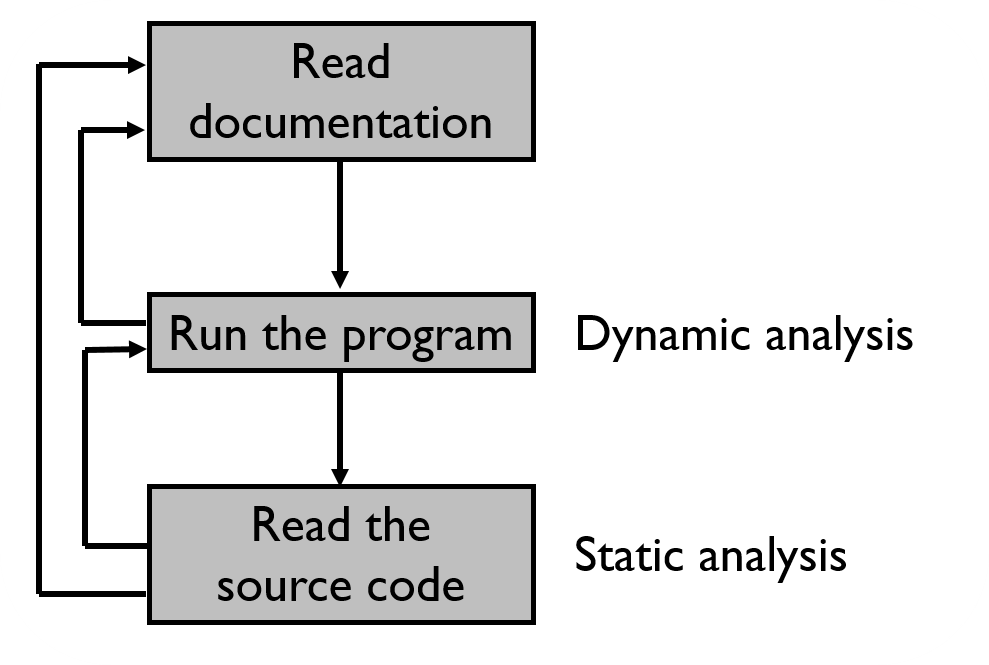

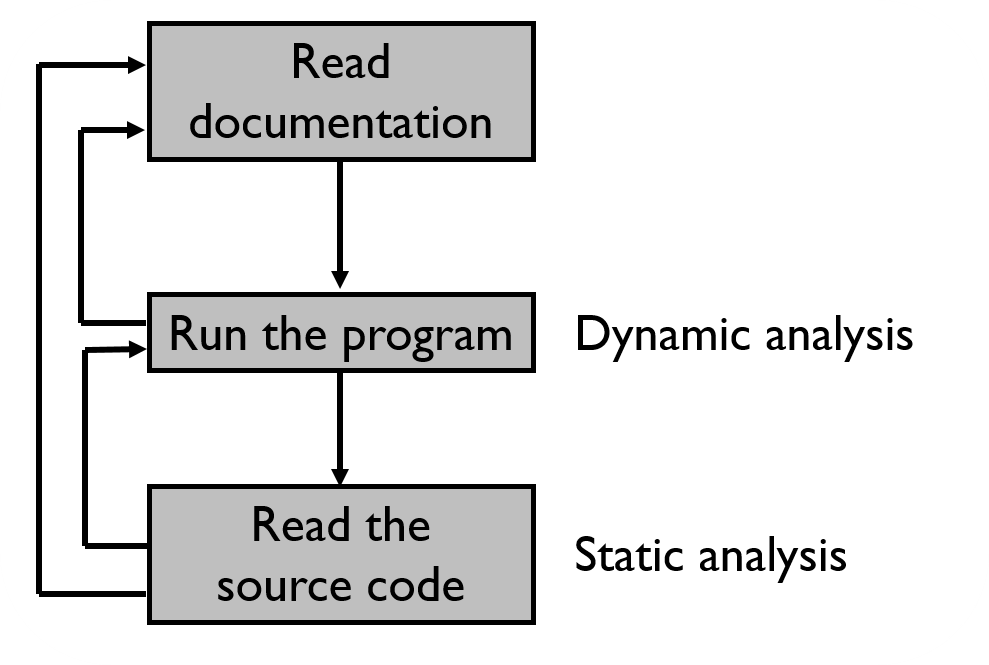

Figure 1: Comprehension process

A fourth-year student in a computing major has probably figured out some of these points. Others will be familiar, but not yet clear. And still others won’t be apparent until you get more experience. And when software engineers say “experience,” we usually mean something bad happened.

Changing software, just like changing your house, is quite different from the initial development. Adding a new room costs more than it would have cost to build that room initially. Changes are constrained by the goals, style, and implementation of the existing system and require changes to existing parts of the system.

Another challenge is the need to understand an existing system to change it. How can the existing code base accommodate the change? What are the potential ripple effects? What skills and knowledge are required to make these changes?

Whether you do it consciously or unconsciously, you will go through several activities every time you change existing software:

These steps are simple with small student projects, but with large-scale production software, if we do not follow these steps consciously and intentionally, we will make mistakes that take lots of time to correct. Note that most well organized software companies will have processes and procedures that must be followed. If not, that could be a sign that projects are not well organized and quality is not valued.

Students usually make simple changes to small programs, often to progams they wrote themselves. This makes understanding the code pretty easy. But the elements of understanding are still the same, whether the program is large or small. First, the programmer must develop domain knowledge about the software’s behavior. Domain knowledge can be gleaned from documentation, end-users, or as a last resort, from reading the program source. Next, the programmer must understand the execution behavior, including the external behavior and how the internal algorithms work. After that, it is essential to learn how different parts of the software affect and depend on each other. Finally, maintenance programmers must learn how the software interacts with its environment.

Figure 1 illustrates a typical process used to understand software. Reading the documentation can save enormous time over reading the source code, but it’s important to recognize that the documentation could be out of date. If the software was built with an agile process, automated tests might be available that document the behavior. They can be very helpful—in fact, the primary goal of most agile processes is to make change easier.

The challenge of understanding an existing program is influenced by many factors, including:

In 1980, computer hardware was slow, memory was expensive, and screens were small. Programming languages were weak, and tools were primitive and often expensive. Not surprisingly, the most important programming concerns were about speed and size.

Today, however, computers are faster, memory is cheap and plentiful, screens are huge, and programming tools get better and cheaper every day. Free IDEs were research dreams in the mid 1980s. The overriding goal of most of these changes is to make it easier to change the program later.

This means

readability is very important.

Even debugging your own code can be painful if you were not tidy to begin with.

(By the way,

the best programmers usually try to be

Another essential habit to support maintenance is to avoid unnecessary fancy tricks. It’s fun to learn nifty tricks with pointer arithmetic, but those tricks have very little benefit, and create a huge amount of maintenance debt. Here are five tips for writing code for humans, not for compilers:

In 1980, the control flow of individual functions dominated the running time of a program, which is exactly why undergraduate courses in CS still emphasize analysis of algorithms so much. Today however, the architecture of the system usually washes out any effect of optimizing individual methods. I once worked on a project where a colleague spent six weeks to optimize methods that accessed data from files—saving almost 4% of execution time. I then looked at his overall design, and found that he was reading the entire file into memory each time through an outer loop! Four hours to make one architectual change saved over 40% of execution time. Moreover nobody could ever understand his micro-optimizations ... not even him.

Back “in the day,” student programs were graded based on comments and formatting. They developed skills that became good habits. We grade automatically these days and often don’t even look at students’ code. That debt is paid eventually, usually by future teammates who struggle to read sloppy code. This brings the question: when should you write comments? Here are a few suggestions:

The last habit will also help you finish faster, result in more reliable software, and leave you with ready-made, free, documentation.

| “There are two ways of constructing a software design. One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies. And the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.” |

| — C.A.R. Hoare |

Developing the following habits will make you more popular among your teammates, more respected by your team leads, and more valuable to your company. Developing these habits in college will make you more efficient, faster, and help you get better grades.

Out-dated documentation can be very dangerous because it can mislead future maintainers. One school of thought says that it’s better to have no information than incorrect information. One solution is to avoid documentation. Another is to be disciplined about updating documentation. Which is better depends on the situation and the people involved. But leaving incorrect document is unprofessional—selfish, lazy, and short-sighted. It is the programmer equivalent of leaving grocery carts in the middle of the parking lot.

This also means we should not over-document. There is no point in documenting the obvious:

setList(List list); // This method sets a list

This comment makes the code worse, not better. But it might help to describe the list and how it’s being set. This could be done in comments ... or even better, with self-documenting names:

readNamesFromFile(List nameList);

Using your language well can also improve the readability. Here are some Java-specific tips.

equals() or hashCode()

o1.equals(o2) is true, o1.toString() should equal o2.toString()

equals() is called on the wrong type, return false, not an exception

super.clone(), not new()

(new() will break if another programmer inherits from your class)

Also remember that immutable objects are your friends in Java. They are simpler, safer, and more reliable. They sacrifice some speed, but not much. Basic types such as keys should always be immutable. After all, their values cannot change. Immutable objects should be declared final so that they can be used just as elementary types. And last but not least, immutable objects are especially useful in concurrent software because they cannot be corrupted by thread interference.

Another really good habit is to increase modularity and reduce coupling as much as possible. The goal of reducing coupling led to most major programming advances in the last 40 years, including macro assemblers, high level languages, structured programming, ADTs, data hiding, inheritance, polymorphism, CASE tools, IDEs, UML, JavaBeans, XML, the web, J2EE, etc. The most common theme is to increase modular components such as methods, classes, files, and packages. It must be possible to describe each component in a very concise way, for example, “this is a set of allowable prices.” If not, you just created maintenance debt.

Think hard about which modules refer to which other modules. It should always be possible to change the implementation without having to change other modules. That is, assume the implementation changes regularly, but the API rarely changes. A very effective way to test the design is to make a few changes early, before the development team breaks up or moves on.

Identity also matters. Think about what an object is, not what the class does. “This is a library book” is clearer and simpler than “this class stores names, prices, and a count of books, and provides access to the information about the books.” A quick rule of thumb is that most class names should be vowels, not verbs. Remember that an object is defined by its state, and the class defines its behavior.

If your classes have lots of switch statements;

they may be trying to do too many things.

Use inheritance,

a base class and children classes,

and use type parameterization (generics).

They are in the language to make your programs simpler.

And when you do that,

please do not confuse inheritance and aggregation.

Inheritance should implement “is-a.”

Aggregation should implement “has-a.”

Finally, keep it simple and stupid. Long names are simple, short names are complicated. Long methods are never simple. Good programmers write less code, not more, and bad designs lead to more and longer methods. Don’t generalize unless you need it. The best programmers can accomplish the same task in half the time, with a quarter of the code, and 10 times more reliably than the worst programmer. And don’t be too proud! The best programmers in college cannot compare to the best programmers with 10 or 15 years of experience. Work hard to turn your future self into that best programmer.

Finally, we can develop lots of simple habits to make our programs more readable. Many of these are commonly included in style guides, and lots of organizations have their own style guides. They may be required or optional. They key is to pick a style and stick with it. The details of the conventions usually not as important as being consistent.

The basics are pretty simple. A study all the way back in the 1960s asked “how far should we indent,” and found very strong evidence that two to four characters is ideal. Fewer than two is hard to see, and more than four makes programs too wide. Never use tabs; they look different in every editor and every printer, so what you see will not be what others see. Even worse is to mix tabs and spaces. Use plenty of white space. That makes names easier to find and read, and is a habit that pays dividends down the road as your eyes age. And never put more than one statement per line. (By the way, I fully realize that most IDEs love tabs. Lots of tools suck.)

A good style guide should cover several aspects:

else statements

And don’t forget to mention language. I will never forget a graduate student who left me with lots of comments in a program. In Korean.

To summarize, the little things that programmers do have a major impact on readability. In turn, readability has a major impact on maintainability, and maintainability is a primary determining factor in the long-term cost of the system. The minor decisions that you make as a programmer determines how much money your company makes. That is what engineering means!

Be tidy, my friends.

Jeff Offutt

George Mason University

offutt@gmu.edu

January 2018